Jizzakh, a lesser-known region of Uzbekistan, is rich in pristine nature, from the Nuratau Mountains and Aydarkul Lake to the Arnasay Wetlands. Faisal Farooq, Multimedia Producer at PTV World and freelance journalist focusing on travel, culture, and people, reveals how nature shapes local communities and supports conservation in Jizzakh, offering a fresh perspective beyond Uzbekistan’s famed Silk Road cities.

- THE UNTOLD STORY WRITTEN IN MOUNTAINS AND SKY

- ESCAPING INTO THE JUNIPERS

- WHEN THE SKY BECOMES THE STAGE

- UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE NURATAU MOUNTAINS

- WHERE HOSPITALITY IS A WAY OF LIFE

- THE DESERT’S MIRAGE

- A TASTE OF JIZZAKH

- SA’D IBN ABI WAQQAS COMPLEX

- TREKKING AND HORSEBACK ADVENTURES

- GETTING TO JIZZAKH

- THE LANDSCAPE YET TO BE TOLD

THE UNTOLD STORY WRITTEN IN MOUNTAINS AND SKY

A few hours’ drive south of Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, the road narrows, the plains open wide, and the horizon begins to wrinkle into ridges.

The air feels lighter here, fresher, as if carrying with it a whisper of something unspoiled. My destination was not a city of turquoise domes and madrassas, but a landscape – raw, vast, and largely forgotten.

Jizzakh is Uzbekistan’s secret – a place where juniper forests give way to desert lakes, villagers open their homes with quiet warmth, and night skies reveal more stars than I had ever seen.

ESCAPING INTO THE JUNIPERS

Leaving behind the bustle of Tashkent, the road to Zomin National Park (Zomin) climbs steadily until the air turns cool and sharp.

It is said that Zomin is the ‘Switzerland of Uzbekistan’, and as I walked under towering juniper trees, I understood why. The slopes ripple with wildflowers in spring, whilst in summer, the park offers relief from the capital’s heat.

I spent an afternoon tracing a shepherd’s path that opened to a sweeping view of alpine meadows where sheep grazed lazily. The light filtered through the junipers in a way that made the scene feel untouched, a place where time had slowed.

But Zomin is not just a retreat; it is part of the vast Nuratau-Kyzylkum Biosphere Reserve, established in 1960 to protect this fragile environment.

Covering more than 10,000 hectares, the reserve shelters mountain ranges, gorges, and even a giant of the natural world – Bobo-Yongok, a walnut tree believed to be 700 years old. Its gnarled trunk stretches nearly three metres across, a living monument older than most empires.

One of the most striking features of Zomin is its vast juniper forests, known locally as ‘archa’. These hardy evergreens thrive on the slopes of the Turkestan Range, clinging to rocky ridges where few other trees can survive.

Some are believed to be over 1,000 years old, their twisted trunks and silver bark weathered by centuries of wind and snow.

In Uzbek culture, juniper branches are often burnt during ceremonies, their smoke believed to cleanse and protect – a tradition that reflects the deep spiritual connection locals have with these trees.

Walking through the forest feels like stepping into a living time capsule. The scent is sharp and resinous, and when the wind rushes through the branches, the air carries a freshness that feels almost medicinal.

For nature lovers and ecotourists, these groves offer not just shade and beauty, but also a chance to connect with one of Central Asia’s most iconic trees.

For photographers, Zomin is pure gold – mist rolling through valleys at dawn, trails that vanish into the horizon, and mountain ridges that seem to invite you further with each step.

WHEN THE SKY BECOMES THE STAGE

Night in Jizzakh feels different. Away from the city’s glow, the sky becomes a theatre of stars.

I set up my tripod on a ridge near the park, and within minutes, the Milky Way spilt across the sky like a brushstroke of silver.

Astrophotography here is effortless – the kind of silence and darkness that photographers travel halfway around the world to find.

Beyond the photos, there was something profoundly humbling about lying on my back, listening to the faint chirp of crickets, and realising that this same sky once guided Silk Road caravans through these mountains.

“Jizzakh is Uzbekistan’s secret – a place where juniper forests give way to desert lakes, villagers open their homes with quiet warmth, and night skies reveal more stars than I had ever seen”

Faisal Farooq

UNDER THE SHADOW OF THE NURATAU MOUNTAINS

From Zomin, I headed west into the Nuratau Mountains, where the landscape turned rugged and ochre, broken only by the occasional flash of green fields.

Here, life slows into an older rhythm, and at Syed Yurt Camp, I had my first taste of Uzbekistan’s nomadic past.

Sleeping in a felt yurt, I woke to the quiet hum of wind across the steppe.

Meals were shared communally – warm bread fresh from the tandir oven, stews simmered with herbs, and endless cups of green tea. At night, the campfire cracked under a sky heavy with stars.

There was no Wi-Fi or traffic – only the raw soundtrack of nature. It was a reminder that sometimes, luxury can be as simple as silence.

WHERE HOSPITALITY IS A WAY OF LIFE

On the slopes of the Nuratau Mountains lies Hayat village, a place where hospitality feels less like a custom and more like a way of breathing.

I stayed in a family homestay, greeted with walnuts, honey, and homemade apricot jam. In the evenings, we sat outside on tapchans (raised wooden platforms) whilst the host family told stories of ancestors who had lived in these mountains for generations.

Hayat is also a gateway to the Nuratau Reserve, home to endangered Severtsov’s sheep and an array of birdlife.

Trekking the reserve, I spotted ibex tracks and heard the echoing call of partridges. But what lingered with me most wasn’t just the wildlife – it was the stillness, the way the mountains seemed to watch over the valley with a kind of quiet dignity.

This is ecotourism in its purest sense – living simply, lightly, and in harmony with the land.

THE DESERT’S MIRAGE

No journey through Jizzakh is complete without a detour to Aydarkul Lake.

Spread across the Kyzylkum Desert, this vast expanse of water appears suddenly, a turquoise sheet shimmering in the midst of sand and steppe.

I arrived as the sun began to fall, turning the lake into liquid fire. A fisherman in a small boat paddled by, his silhouette swallowed by the setting light. Migratory birds wheeled overhead, their calls carrying across the still surface.

Later, as the desert night cooled, I sat by the shoreline listening to the gentle lap of water against the sand – a sound so rare in these arid lands that it felt almost sacred.

A TASTE OF JIZZAKH

Food in Jizzakh carries the warmth of its people and the depth of its traditions.

The region is famed for its king-size samsa — golden pastries stuffed with lamb, onions, or pumpkin, baked in the walls of a clay oven until crisp on the outside and tender inside.

Fresh tandir bread, warm and smoky, accompanies nearly every meal. But the true culinary emblem of Jizzakh is tandir kabob, a dish born from the nomadic way of life.

Marinated with salt – sometimes even pine needles – and slow-cooked in clay tandirs until the smoke and heat transform the meat into something both tender and aromatic, this kabob is best tasted twice: once hot, when the juices run rich, and once cold, when the flavours deepen into something altogether different.

To eat in Jizzakh is not simply to dine, but to share in a tradition that has travelled across centuries of steppes and mountains.

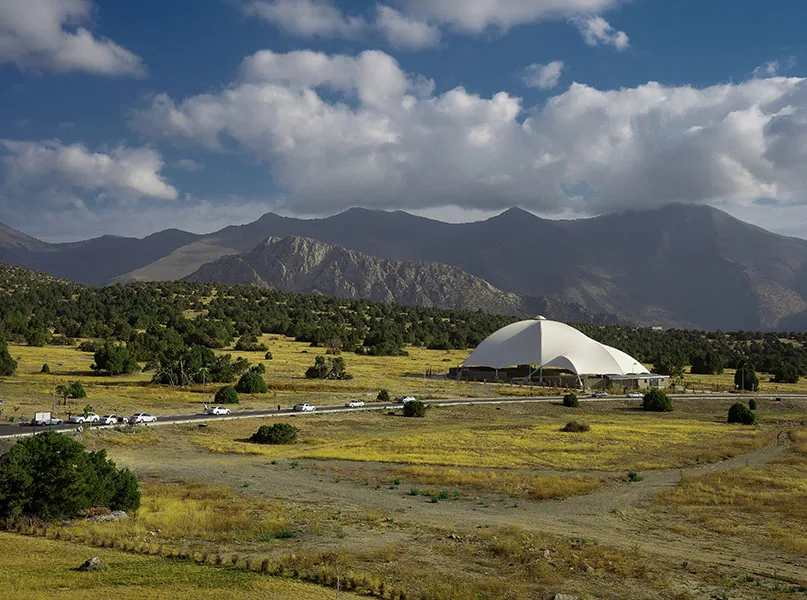

SA’D IBN ABI WAQQAS COMPLEX

Jizzakh is not only about mountains and meadows; it also carries deep spiritual echoes.

On the edge of the region stands the Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas Complex, a sacred site dedicated to one of the companions of the Prophet Muhammad.

Local tradition holds that Sa’d ibn Abi Waqqas once passed through these lands, leaving behind a legacy of faith and resilience.

Today, pilgrims and travellers alike visit the complex for quiet reflection, walking amongst its courtyards and listening to the stories told by caretakers.

Set against the backdrop of rolling hills, the site blends history, spirituality, and landscape – a reminder that Jizzakh’s story is not just written in nature, but also in the faith of its people.

“Few visitors make it here, and perhaps that is Jizzakh’s greatest gift. It is a region that remains untold – a landscape still writing its own story, waiting for those willing to venture beyond the well-worn Silk Road path”

Faisal Farooq

TREKKING AND HORSEBACK ADVENTURES

For active travellers, Jizzakh offers some of Uzbekistan’s most rewarding outdoor experiences.

Trails range from easy half-day hikes through juniper forests to multi-day treks across the Nuratau Mountains, where ancient rock carvings and sweeping ridgelines mark the way.

Horseback riding remains a traditional way to explore these landscapes – winding through gorges, climbing mountain passes, or tracing old caravan routes.

Whether on foot or horseback, the region’s blend of raw nature, wildlife encounters, and cultural stops at mountain villages makes every journey feel like an expedition into an untold corner of Uzbekistan.

GETTING TO JIZZAKH

Reaching Jizzakh is easier than ever thanks to its central location in Uzbekistan.

The region lies about three to four hours by road from Tashkent, Samarkand, or Bukhara, making it an ideal stop between the country’s historic Silk Road cities.

Comfortable trains connect Jizzakh with Tashkent and Samarkand, whilst shared taxis and buses run daily routes through the mountain passes and valleys.

For those flying in, the newly upgraded Jizzakh Airport offers a convenient gateway just a short drive from Aydarkul Lake and the Nuratau Mountains, bringing adventurers closer than ever to the region’s wild landscapes.

THE LANDSCAPE YET TO BE TOLD

Travel in Jizzakh is not about ticking off monuments.

It’s about slowing down, watching, and listening. It’s the laughter of children chasing goats through mountain meadows. It’s the shock of cold water on your hands in a desert lake. It’s waking to the silence of a yurt, with the peaks of the Nuratau Mountains rising in the distance.

Few visitors make it here, and perhaps that is Jizzakh’s greatest gift. It is a region that remains untold – a landscape still writing its own story, waiting for those willing to venture beyond the well-worn Silk Road path.